Superstition, cautious optimism, overwhelming rage and complete distrust, these are the range of emotions elicited from residents of Lagos state in an anonymous online survey on the Eko Atlantic City project. From village-dwelling market women to well-educated elites in Nigeria and abroad, most express concern over the ability (or the lack thereof) of the current government to operate and maintain such a significant capital project or handle disasters that can potentially occur as a consequence.

Since inception, the city, which aims to accommodate a quarter of a million people, has been marketed as a cutting edge, high-end sustainable development. According to the developers the city’s planners have committed to minimizing Eko Atlantic’s carbon footprint with the use of environmentally-efficient construction methods and locally sourced materials where available and appropriate.”

Also promised are extensive public roadway transportation, in conjunction with intra-land waterways and heliports. These cursory statements, along with the obvious reclamation of eroded land, consists all of the sustainable design references listed in the city’s marketing brochure. The document is inundated with un-cited claims and statements that promise enormous commercial gains, promising foreign investors and buyers the opportunity to ‘harvest the potential of Africa’ – a phrase that brings to mind the 19th century western scramble for the continent. There is no definite commitment to the implementation of sustainable design strategies that can also help resolve ecological and socio-cultural challenges (such as air pollution and housing for low-income earners) which are prevalent in Lagos.

Going further, a personal review of the city’s regulations for specific plots of land in its downtown area did not reveal any strong focus on green design issues. The guidelines provided were generic. There were requirements for greenery in each lot but issues related to site permeability, storm-water quantity control, construction activity pollution prevention, air, noise and light pollution reduction were not addressed.

Also, when further challenged on the sparseness of clearly-defined sustainable design measures, in May 2013 representatives of the city’s backers stated unequivocally that such design measures are at best tangential to their ultimate goal of profitability. This unfortunate response to a very pertinent and global issue confirmed the need to intervene by re-envisioning Eko Atlantic City in a more sustainable fashion. One might argue that the very existence of the city in itself is unsustainable, but the unchanging fact is that at least 50% of the area intended for reclamation has already been sand-filled, roads have been built, drainage lines buried and some lots have been bought. The Eko Atlantic City seems here to stay therefore, perhaps it is better to focus on ‘making a bad thing good’…or a little less bad.

Consequently, in July 2013 the Code Green Campaign was initiated, due to the strong reaction perceived amongst construction industry professionals surveyed for their views regarding the city. The aim is to develop sustainable guidelines for the Eko Atlantic City in the hope that these can be adopted for future construction projects. Bearing in mind the City’s proponents’ unapologetic focus on financial gains, the Code Green group decided to approach the initiative from an investor’s perspective. It determined that true sustainability in an emerging economy such as that of Lagos must have a strong economic component, along with ecological and socio-cultural aspects. Typical challenges that investors may face during a project delivery process –from land acquisition to building occupancy– were identified and then addressed from a sustainability point of view. This means ecological concerns and socio-cultural issues were noted, while attempting to solve mostly economic and profitability challenges.

The first major challenge identified was funding costs. Most Nigerian banks provide construction loans at interest rates of between 18% - 30% per annum. Typical high-rise construction projects often take at least two years to develop, implying that at minimum, a typical investor would have accrued an additional 36% in interest during the project delivery process. The challenge therefore, was to investigate faster, greener ways to construct high-rise buildings so that loan interest accruement and construction activity pollution decreases while building envelope, energy and construction efficiency increases.

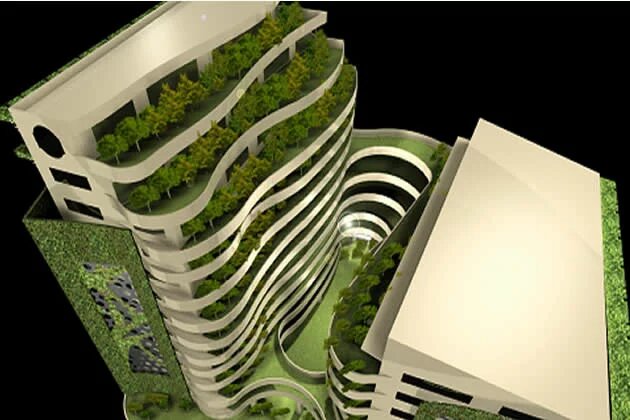

One of the investor-driven perspective explored was maximization of leasable space. The lot regulations reviewed indicated that each skyscraper must step back as it goes higher, in order to minimize shadows cast over other buildings. What this means for investors though, is that as the building goes higher, there is less square footage to monetize. The task therefore, was to find ways in which the ‘lost space’ could be utilized and even monetized. One idea that gained traction was to move all ‘sociable’ communal spaces (lobbies, staff-break rooms, cafeterias, non-private meeting rooms, or restaurants) to the perimeter of the building in balconies and porches that overhang the lower floors. These balconies can be vegetated, providing shade and reducing solar heat gain, purifying the air and providing additional opportunities for natural ventilation in other spaces. They can also be expressed as a form of vertical urban farming, where consumable vegetables are planted. Since these gardens will be cantilevered spaces, technically, the exterior walls of that floor will begin where the lot regulation requires, providing more money-generating spaces within the floor area. If every skyscraper in Eko Atlantic City were to adopt this strategy and become a vertical urban farm, then a significant chunk of food security issues and urban poor challenges in neighbouring low-income areas may be addressed.

This vision for a truly sustainable Eko Atlantic City is a huge but implementable one. Over the last decade, green design measures and products have undergone significant testing and development and are no longer a ‘grey area’ when it comes to cost efficiency and validity. If the economically supportive measures discussed above become mandatory and are implemented, then Eko Atlantic City may be well on its way to being the most sustainable city in the Sub-Saharan Africa region – and that, we are sure, is a tag line its developers would like to take to the bank.

Read the full article

Download the full report of the Code Green Campaign